Often organizations determine that a suitable time to adopt a new taxonomy is in conjunction with adopting a new system for its implementation, such as a content management system (CMS) or digital asset management system (DAM). They can budget taxonomy design and development services as part of the consulting services needed for the content migration and system implementation project, and they can improve and optimize the taxonomy for its new implementation and use.

There is the question of timing, though. Recently, a prospective consulting client asked me whether the new taxonomy should be developed prior to the selection and implementation of a new system or afterwards. Ideally, both the taxonomy project and the CMS or DAM adoption can happen simultaneously. However, the design and development of a taxonomy takes less time (typically 3-4 months) than the adoption of a new CMS or DAM. Altogether, a system selection, with a trial or a proof-of-concept project, implementation, data/content migration, and user training, can take 6-18 months.

Benefits of Taxonomy Development Prior to System Adoption

The primary benefit of developing a taxonomy prior to system adoption is that you can make it a system requirement that the new system supports the taxonomy that you have designed to best serve your users, your desired tagging method, and the nature of your content. These criteria should take precedence over designing a taxonomy to fit the requirements (or limitations) of a CMS or DAM.

Over time, your organization will adopt other systems, and the taxonomy should be suitable for multiple systems, rather than being system specific. Especially if you have an enterprise (enterprise-wide) taxonomy as your eventual goal, designing your ideal taxonomy first should be your approach. If one system cannot take advantage of all features of your taxonomy, another system may. There are also usually development work-arounds to get the full use out of your taxonomy.

Benefits of Taxonomy Development After System Adoption

A CMS or DAM has a variety of functions, and tagging and retrieval of content with a taxonomy in only one of those functions. Workflow management, rights management, authoring features (for CMS) and image/video editing features (for DAM) tend to matter more than taxonomy use among the requirements for a system. You can make “good support of taxonomy management and tagging” a requirement for your new CMS or DAM without getting into the specifics.

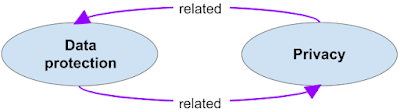

Adding features a taxonomy (such as polyhierarchy, related-concept relationships, end-user scope notes, different sets of synonyms/alternative labels to support each tagging and searching) if the system you later adopt does not support them is a waste of time and resources. It’s better to wait until a system in selected and implemented before fully designing a taxonomy.

Iterative Taxonomy Design Approach

When implementing a new taxonomy with a new system, the ideal approach is to spread out the taxonomy design and development tasks over the phases on the system selection and implementation process.

You should consider basic taxonomy requirements early in the system selection process. To do this, you might categorize different taxonomy support features as essential and nice-to-have. The method of tagging (automated, manual, automated with human review, and a mix) needs to be determined as both a system requirement and as a factor in the design of the taxonomy.

Then during the lengthy process of system testing and selection, information-gathering work for the taxonomy may take place. This involves stakeholder interviews, user focus groups or brainstorming sessions, content analysis, and review of existing/legacy taxonomies and other controlled vocabularies. Draft versions of portions of the taxonomy, without all features, may be created and reviewed, prior to the system selection decision.

After the CMS or DAM is selected and is in the process of being implemented the taxonomy design can be refined with features that the new system can support, and then the taxonomy can be fully built out. The new taxonomy can also be tested in the new system for its suitability for tagging and retrieval, and final enhancements are made based on the test results. The documentation of the taxonomy, including guidelines for its maintenance (a governance plan), should be started early in the taxonomy design process, but additional system-specific documentation is created after the new system is implemented.