When I spoke about taxonomies at the recent SLA (Special Librarians Association) annual conference, I was asked how a taxonomy differs from a subject heading scheme. Librarians are very familiar with subject headings, which are used to catalog books and other library materials. This is an interesting question, which I answered briefly in my presentation session, but I’d like to explain further.

I have previously written about how a taxonomy differs from a classification in “Classification Systems vs. Taxonomies” Taxonomies are more similar to subject heading schemes. Libraries use both classification systems (such as the Dewey Decimal), which are for determining the physical location of books and other library materials on shelves based on their codes, and subject heading schemes (such as Library of Congress Subject Headings), which are used to identify books and other materials by their specific subject matter. The same subject could be used to catalog books and materials of different types (nonfiction, fiction, sound recordings, children’s) with very different classifications.

How Taxonomies and Subject Heading Schemes are Similar

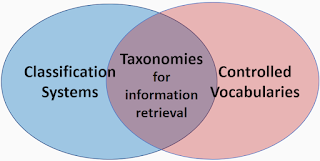

Taxonomies and subject heading schemes are both considered

types of controlled vocabularies, and they share similar uses and features.

They both serve users who are looking up subjects to find information or

resources available on the subject, rather than (or not yet) for identifying

the physical location of the resource. In addition, they both:

- have structures, but their focus is on the concepts

- can be both searched and browsed

- exist for both general and specific subject domains (Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) published by the National Library of Medicine is an example of a specific subject-domain subject heading scheme.)

- have some structured, thesaurus-type of relationships between terms, including broader/narrower, and related.

- bring together different names, as synonyms/alternative labels/nonpreferred terms/used for terms

- may include named entities (proper nouns for people, organizations, or geographic places) alongside topical subjects

- may have scope notes on select terms

How Taxonomies and Subject Heading Schemes Differ

With so many similarities, one might wonder if there are any differences between subject heading schemes and taxonomies.

Subject heading schemes and taxonomies have different histories and originally different formats. Subject heading schemes were designed for the print format and have been adapted to digital environments, whereas information “taxonomies” as we know them have existed only after the emergence of digital navigation and search systems.

Structural Differences with Subdivisions

The name “subject headings” refers to the traditional browsable display of headings in an index, and under headings may appear sub-headings or subdivisions to further refine multiple references/citations/linked results. This structure is the main difference between subject heading schemes and taxonomies. The heading-subheading/subdivision structure is characteristic of back-of-the book indexes and indexes to articles when such indexes previously appeared in print, although it is still used online.

A subject heading may be subdivided by the addition of

different types of subdivisions: topical, geographical (such as a country name),

chronological (such as century, decade or war time), and form (for the content

type, such a Periodicals). Some topical subdivisions are rather generic and can

be applied to many headings, such as “Management,” “Research,” or “Law and

legislation,” but most are specific to only a limited number of headings. For

example, the subdivision “Lighting” is to be used under headings for

structures, rooms, vehicles, installations, etc. See the full list of Library of Congress subdivisions.

The way that subdivisions refine a heading can be compared to the function of facets in a faceted taxonomy, which was noted by someone in the audience of my conference session. (See also the post “Faceted Classificationand Faceted Taxonomies.”) Subdivisions and facets are both aspects of something. That does not mean, however, that a faceted taxonomy and a subject heading scheme are the same.

The structure of a faceted taxonomy has facets at the top-level, and the facets are relevant to a specific set of content, so they are aspects of the content, rather than aspects of a heading term.

There can be hierarchies of terms within a facet of a faceted taxonomy, but subdivisions do not have internal hierarchy. Instead, subdivisions may subdivide each other, but this is more like a prescribed navigation path, and they must follow a standard sequence. For example:

English literature—20th century—History and criticism

Application Differences of Subdivisions vs. Attributes

Another facet-like implementation of taxonomies is to have attributes to refine the search results of a specific term within a hierarchical taxonomy. Attributes are common in e-commerce taxonomies, which involve a hierarchical taxonomy for product categories and attributes for product features. Attributes are more like subdivisions, in the way that they refine topics from the hierarchical taxonomy, but they are applied (tagged) differently than subdivisions.

The combination of a subject heading and a subdivision is done at the time of indexing an article or cataloging a book, and there are rules about which combinations are permitted. The combinations are indexed as if they were a single compound concept. Catalogers are required to use established heading-subdivision combinations and cannot just make up their own. Any string of multiple subdivisions must be applied in a prescribed order, such as geographic-topical-chronological-form for Library of Congress Subject Headings that are topics authorized for geographic subdivision.

Unlike the practice of cataloging or indexing with subject headings and subdivision taxonomy terms and attributes for refinement are:

assigned more independently of each other, although the type of taxonomy term may restrict which attributes are available

have a greater number of attribute types available and tag a piece of content with values from most or all of the attribute types

may even have more than one attribute value of the same type may be applied (such as an item having two colors)

have no ranked order to apply attributes or to search on them

Convergence of Subject Headings Schemes and Taxonomies

While subject heading schemes and taxonomies have traditionally had different styles, they have become more similar in more recent decades.

Many subject heading schemes and taxonomies have both adopted thesaurus features. Originally, the Library of Congress Subject Headings had only See (Use) and See also relationships (like in an index), but in 1987 it adopted thesaurus relationships of broader term/narrower term, and related term in place of See also. Meanwhile the differences between taxonomies and thesauri have also been blurred, as taxonomies may have related-term relationships, and thesauri may have an over-arching hierarchical structure. The leading reason taxonomies and thesauri are difficult to distinguish, in my opinion, is because the same software tools are used to develop and manage both, and the software makes no distinction between “taxonomy” and “thesaurus.”

Another way in which subject headings have become more like taxonomies is that subject headings may be used without subdivisions. This is increasingly common as subject headings get reused in search and retrieval systems which do not support the complexity of subdivisions. For example, newer online publishers of medical information have adopted Medical Subject Headings without their subdivisions, which are still used by the National Library of Medicine. Additionally, auto-tagging is not easily done with multiple levels indexing. Without subdivisions, subject heading schemes are essentially the same as taxonomies, as long as they have a hierarchical structure.

Conclusions

Taxonomies have similarities and differences to both classification systems and to subject heading schemes. In fact, I would say that the modern information taxonomies have inherited features of both. Taxonomies are not always well defined, but they are flexible and adaptable to business needs.

Controlled vocabularies have existed for a long time, but their applications are becoming more varied. This has led to differences and also convergences of their features. Nevertheless, certain controlled vocabularies are more common in certain implementations. Subject heading schemes remain common in libraries, whereas taxonomies are more common in business and commercial implementations.