I usually explain that a taxonomy is a structured kind of controlled vocabulary, which is list of terms (or concepts) usually used to tag content to aid in its retrieval. The structure can be hierarchical, faceted, or a combination. Other people have defined taxonomies for a general audience in more simplistic ways as a kind of hierarchical classification system. So, while a taxonomy has two main features (naming and structure), my preferred definition has focused on the controlled vocabulary and naming aspect, whereas other definitions focus on the hierarchical classification aspect of taxonomies. However, a taxonomy and a classification system are not necessarily the same. While it is understandable that a definition is simplified for a general audience, it should not be simplified to the extent of being misleading.

I have blogged previously on the differences between taxonomies and classification systems, so I won’t repeat all the differences again. The main point is that a classification system is generic and rigid and is intended to be used widely, such as the Dewey Decimal Classification for libraries, whereas a taxonomy tends to be customized for a particular use case and context and is flexible and undergoes changes.

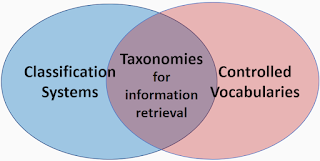

Meanwhile, there are also a few well-known classification systems that are called “taxonomies,” such as the Linnaean taxonomy of organisms and Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. These seem quite different from the information-retrieval type of taxonomy. The Linnaean hierarchical levels have names (Kingdom, Phylum, Class, etc.). The relationship of the hierarchical levels to each other are not all of the thesaurus standards: generic-specific, generic-instance, or whole-part. Rather, the Linnaean taxonomic relationship are generic-specific only, or more precisely that of member of class or subclass. Bloom's taxonomy has a completely different hierarchical model that does not follow thesaurus standards at all.How does a taxonomy of concepts for information retrieval relate to a scientific taxonomy? They are similar, and the differences are not so great that there should be considered different meanings of the word “taxonomy.” If we consider that taxonomies are systems to name and organize things hierarchically, then a taxonomy for information retrieval, comprised of terms for tagging and retrieving content (documents, images, etc.), can be considered a taxonomy of a controlled vocabulary, in contrast to taxonomies of things, such as organisms. This is a slightly different perspective than to consider a taxonomy as a kind of controlled vocabulary, as I previously had. The following diagram illustrates a possible way to consider how information-retrieval taxonomies related to classification systems and controlled vocabularies.

Several kinds of knowledge organization systems are defined by their published standards. For thesauri, there are ANSI/NISO Z39.19 and ISO 25964. For terminologies, there is ISO/TC 37/SC 3 and other related standards. For ontologies, there is OWL (Web Ontology Language) from the W3C. There is no standard, however, specifically for “taxonomies” or even for “classification systems,” which is a reason why these remain difficult to define. The designations “classification system,” “classification scheme,” and “taxonomy” have been used interchangeably.

Wikipedia provides the definition at the entry for Taxonomy: “A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types.” But then it goes on to say, “it may refer to a categorisation of things or concepts.” Thus, an information-retrieval taxonomy is a categorization of concepts (also called terms in a controlled vocabulary). It is not a classification system, since the goal is not to classify things, not even the things tagged with the taxonomy concepts, but rather to organize the set of concepts that have been identified as appropriate for tagging and retrieving a set of content.