What is faceted classification?

|

| Facets for jobs |

Classification is about putting an item, such as a content item (document, page, or digital asset) into a class or category. If it’s a physical object (a book) it goes into a shelf of its class. In faceted classification, an item cannot physically be in more than one place, but it can still be “assigned to” more than one class. So, while the book itself can be on only one shelf, the record about the book can be assigned to more than one class.

Faceted classification assigns classes/categories/terms/concept from each of multiple facets to a content item, allowing users to find the item by choosing the concepts from any one of the facets they consider first. Different users will consider different classification facets first. Users then narrow the search results by selecting concepts from additional facets in any order they wish, until they get a targeted result set meeting the criteria of multiple facet selections. The user interface of faceted classification is sometimes referred to as faceted browsing.

History of faceted classification

The idea of faceted classification as a superior alternative to traditional hierarchical classification, whereby an item (such as book or article) can be classified in multiple different ways instead of in just a single classification class/category, is not new. The first such faceted classification was developed and published by mathematician/librarian S.R. Ranganathan in 1933, as an alternative to the Dewey Decimal System for classifying books, called Colon Classification (since the colon punctuation was originally used to separate the multiple facets). In addition to subject categories, it has the following facets:

- Personality – topic or orientation

- Matter – things or materials

- Energy – actions

- Space – places or locations

- Time – times or time periods

Although it was not adopted widely internationally due to its complexities in the pre-digital era, colon classification has been used by libraries in India.

In the late 20th century, digital library research systems based on databases enabled faceted classification and search, with different fields of a database record represented in different search facets. Users interacted with through an “advanced search” form of multiple fields. Faceted classification and browsing gained widespread adoption with the advancement of interactive user interfaces on websites and in web applications in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Thus, facets started being displayed in more user-friendly ways that were no longer “advanced.”

Structure of facets

It’s not necessary to follow Ranganathan’s suggested five facets, but that’s a good way to get thinking about faceted classification. Another way to look at faceted classification is to consider a facet for each of various question words: What, Who, Where, When

- What kind of thing is it – content type

- What is it primarily about - subject

- Who is it for or concerns – audience or user group

- Where is it for/applicable, or where it depicts (media) – geographic region

- When it is about – event or season (not date of creation, which is administrative metadata, instead of a taxonomy concept)

The additional question words of “why” and “how” are relevant in some cases, but less common. An individual content item typically does not address all of these questions, but usually addresses more than one. When creating facets, most of the facet types should be applicable to most of the content types.

Another good way to think about faceted classification is to put the word “by” after each facet, to suggest classification and filtering “by” the aspect type. A logical and practical number of facets tends to be in the range of three to seven.

A standard feature of facets is that they are mutually exclusive. A concept/type belongs to only one facet. This is typical practice for the design of classification systems. The difference is that in faceted classification it is merely the concept/type/term that belongs to just one facet, not the content item or thing itself that would belong to only one classification in traditional classification systems.

When a faceted taxonomy is not for classification

The design, implementation and use of facets to construct or refine searches has become so popular that it is no longer used just for classification aspects. Rather, a faceted taxonomy design may be used for any faceted grouping of concepts for search or metadata types that are relevant for the content and users.

Faceted classification is intended to classify things that share all the same facets. For example, all technical documentation content has a product, feature, issue, and content type, so these are faceted classifications. But with more heterogeneous content, facets are not universally shared. While the facets may still be useful tool, it would be best not call it faceted classification when facets are applicable to only some content types.

While faceted classification tends to be quite limited in the number of its facets, non-classification faceted taxonomies, whether based on subject types or separate controlled vocabularies, could result in a rather large number of facets.

Faceted taxonomies that would not be considered faceted classification include those where multiple facets are created for organizing and breaking down subjects or when multiple facets are created for reflecting multiple different controlled vocabularies. These faceted taxonomies stretch the meaning of “facet,” since the facets are not necessarily faces, dimensions, or aspects, but simply “types” suitable for filtering.

Facets for organizing subjects

In faceted classification we assign an object or content item to multiple different classes. However, for classification, these classes are relevant to the content item as a whole. This contrasts with indexing or tagging for subjects or names of relevance that occur within a text or are depicted within a media asset. These names and subjects can be grouped into facets for filtering/limiting search results, without being about the “classification” of the content item. This is common for specialized subject areas. Faceted taxonomies provide a form of guided navigation and are easier to browse and use than deep hierarchical taxonomies, so a large “subject” taxonomy could be broken down into specific subject-type facets.

Examples of specific subject-type facets include:

- Organization types

- Product types

- Technologies

- Activities

- Industries

- Disciplines

- Job roles

- Event types

- Topics

The “Topics” facet is then used for the leftover generic subject concepts that do not belong in any of the other specialized facets. Unlike faceted classification, each facet is applicable to only some content items.

Any content item could be tagged with any number of concepts from any number of these facets. The facets make it easier for user to find taxonomy concepts and combine them. But the facets are not for “classifying” the content.

While faceted taxonomies should also ideally be mutually exclusive, in contrast to the principle of faceted classification, the occasional exception of a concept belonging to more than one subject-type facet (question word of “What”) does not create a problem in search. For example, the same concept Data catalogs, could be in the facet Product Types and Technologies, as long as this type of polyhierarchy is kept to a minimum to avoid confusion. This would not be considered a case of classic polyhierarchy, because it’s not simply a matter of different broader concepts, but rather different facets or concept schemes. It is an attempt to address a different focus or approach to the topic that results it being in more than one facet, offering an additional starting point for searchers.

Facets for organizing controlled vocabularies

Faceted filters/refinement may be based on different controlled vocabulary types: one or more of term lists, name authorities, and subject thesauri/taxonomies. The “facets” are based on how the set of multiple controlled vocabularies is organized rather than based on “aspects” of the content.

Facets could be used for any controlled vocabulary filters that are logical, such as:

- Named people (mentioned/discussed)

- Organizations (mentioned/discussed)

- Products/brands (mentioned/discussed)

- Divisions, departments, units (mentioned/discussed)

- Named works/document titles (mentioned/discussed)

- Places (mentioned/discussed)

- Topics (mentioned/discussed)

Because these facets reflect controlled vocabularies of concepts used to tag content for relevant occurrences of the subject/name and not for classification of the content, this kind of faceted taxonomy would not be considered faceted classification. There could, however, be additional faceted classification types, such as content type.

The Topics facet could contain a large hierarchical taxonomy or thesaurus. As such, this faceted search/browse structure, may not even be considered a “faceted taxonomy,” but rather merely a faceted search interface to a set of taxonomies. Thus, there is even a nuanced difference between a faceted browse UI that utilizes at taxonomy (among other controlled vocabularies), and a “faceted taxonomy.”

Facets for heterogeneous content

Finally, whether a faceted taxonomy is considered an implementation of faceted “classification” or not may depend on the context and type of content. If the content is homogeneous and all items share the same facets, then it may be considered faceted classification, but if the content is heterogeneous, and the facets are only relevant to some content, then it would not be considered classification.

Consider the following example of specialized subject-based facets for the field of medicine:

- Diseases or conditions

- Body parts (anatomy)

- Sign and symptoms

- Treatments

- Patient population types

If all the content comprised just clinical case studies, then these facets actually could be considered faceted classification, since they all apply to nearly all the content and are aspects of the content. The content is classified by these facets. On the other hand, if the content dealt with all kinds of documents that had something to do with health or medicine, then these facets would not be for classification of the content but rather just for grouping of subjects for search filters.

When faceted classification is not a taxonomy

|

| Attributes for computers |

Taxonomies are primarily for subjects and may include named entities. Content types/document types may also be included in the scope of taxonomy. There exists additional metadata that may be desired for filtering/refining searches that is out of scope of a definition of taxonomy. This includes date published/uploaded, file format, author/creator, document/approval status, etc. If it is important to the end users, these additional metadata properties could be included among the browsable facets and be considered classification aspects.

Attributes are a form of faceted classification, but a set of attributes is not really a faceted taxonomy. Often ecommerce taxonomies are presented as examples of faceted taxonomies. In fact, ecommerce taxonomies tend to be hierarchical, as they present categories and subcategories of types of products for the users to browse. At lower, more specific levels of the hierarchy, the user then has the additional option to narrow the results further by selecting values from various attributes that are shared among the products within the same product category. These include color, size/dimensions, price range, and product-specific features. I would not consider numeric values to be a taxonomy, but some attributes, such as for features, are more within the realm of taxonomies. Whether these should be called facets or attributes is a matter of debate. More about attributes is discussed in my past blog post “Attributes in Taxonomies.”

Conclusions

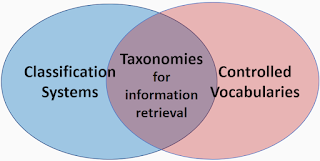

Not all faceted taxonomies are faceted classifications, but some are. Not all faceted classifications are taxonomies, but some are. The differences are nuanced, and end-users may not care nor need to know these naming distinctions, as long as the taxonomist should. Having a deep understanding of facets helps taxonomists and information architects design the facets better. The goal is to serve the users with the most suitable faceted design to serve their needs and accommodate the set of content.