Taxonomies need to be custom-created for their purposes to be most effective. Basically, a taxonomy comprises the concepts or terms that reflect the subject domain of the content that will be tagged and retrieved with the aid of that taxonomy. Taxonomies must also be customized to the requirements (or limitations) of the implemented search technology and the user interface, and ideally the taxonomy is also customized to the needs and preferences of the users. This includes taxonomy design aspects of size, degree of detail, use of synonym/variants, use of hierarchy, and implementation as facets.

Taxonomy customization usually focuses on the concepts/terms/labels

and not so much on the exact hierarchy of grouping narrower concepts under

broader concepts, other than perhaps limiting the number of hierarchical

levels. While the selection and definition of concepts depends on the context

of the content, the hierarchical relationships between concepts are typically independent

of any specific content and are usually dependent only on the context of the

taxonomy itself. Such a context-independent

hierarchy is what enables a single taxonomy to be used for multiple different

content items of different content creators. This is also the approach used in

designing classification systems, which are intended for broad, generic use.

Why Customize Hierarchy

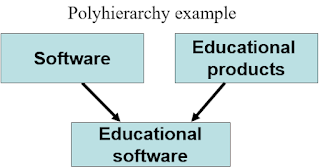

However, a customized taxonomy may be designed for a rather specific body of content, and then the hierarchy may depend on the context of that overall body of content, if not the specific content items. For example, the concept “Piano” is often considered narrower to “Musical instruments”, but in certain contexts it may be narrower to “Furniture,” such as for the contexts of interior design, furnishing a bar or restaurant, or for moving and storage services. Furthermore, I would not always recommend that “Piano” be narrower to both broader concepts in the same taxonomy (a taxonomy feature known as “polyhierarchy”), because the same taxonomy might not be used for both contexts. It depends.

When structuring a taxonomy hierarchy, the use and purpose

of the hierarchy needs to be considered. A hierarchy is not created simply

because it’s a taxonomy and thus traditionally has hierarchy. Possible uses of hierarchy include:

- Supporting browsing and navigation to guide users to the desired concept.

- Providing context for concepts to support tagging, whether manual or automated.

- Enabling “recursive” or “rolled up” retrieval, so that a user’s selection of a concept retrieves not only what was been tagged to that concept but also what has been tagged to all of its narrower concepts, too.

- Enabling expansion of a search, so that if there are too few or no results for a specific concept, the retrieval set can be expanding to content tagged with the broader concept and/or other narrower concepts of it.

- Instructing users on the appropriate classification and organization of information

Usually, the same hierarchy can support all of the above

goals, although occasionally there are conflicting needs.

Customizing Hierarchy Example

The need for customizing hierarchy became especially clear to me in a recent taxonomy consulting project I did for the business of event venue space rentals. Types of spaces (structures, rooms, etc.) were grouped under broader concepts by their potential use, rather than by structural type. To a lesser extent, events or activities for spaces were also sometimes grouped by the type of space that might be suitable. For example, a generic taxonomy might include “Dance class” and “Technical training” both under the same broader concept for “Classes/training,” but because these different types of classes need different kinds of spaces, in this taxonomy they were put in different parts of the taxonomy hierarchy. “Dance class” was made narrower to “Dance event,” and “Technical training” was made narrower to “Training.”

The hierarchy of concepts used in a taxonomy to tag images may also be structured differently than a taxonomy for tagging text content. In this case, for example, broader concepts for grouping others had been created of “Small meeting” and “Large event,” which may not seem logically needed when the range in number of guests was an additional search attribute/filter. However, these concepts are quite useful for tagging images that may depict a small or large event but do not utilize counts of people. Another example is grouping together under the same broader concept the activities of music rehearsals/practices along with music performance events under the same broader concept of “Music events.” Although the activities of organizing rehearsals and organizing performances are quite different from each other, the venues that are suitable for each and their images are similar.

Despite their similarities in scope and concepts, a taxonomy for venue rentals should not be the same as a taxonomy for real estate of long-term lease or sale of properties (focusing on the space but agnostic to the use), nor for events management (focusing on the details of events and less so on space), nor equipment sales and rentals (focusing on the equipment and less on the use). Even when the concepts are the same, the hierarchy may differ. While the inclusion of concepts and their labels should consider the content, the design of the hierarchy should consider the taxonomy’s use.