| |

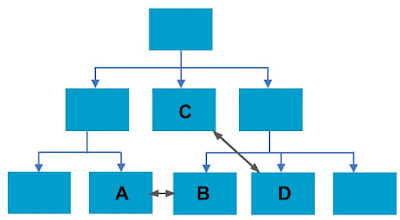

| A and B are related; C and D are related. |

An over-simplistic distinction between taxonomies and thesauri is the presence of associative relationships, although I would disagree, because taxonomies can have associative relationships, and there are other structural design differences between taxonomies and thesauri. (See my past blog posts Taxonomies vs. Thesauri and Taxonomies vs. Thesauri: Practical Implementations)

The associative (related) relationship is a generic, nonhierarchical, symmetrical (same in both directions), reciprocal relationship between pairs of terms/concepts in a thesaurus or taxonomy. "Related concept" actually refers to a kind of relationship, not a kind of concept. The following figure illustrates that Data protection and Privacy are related.

It is true that many taxonomies do not have associative relationships. This is for various reasons. The function of the taxonomy in the user interface may not require the support of related concepts, such as when the taxonomy is displayed only as facets for refining results or only as type-ahead taxonomy term suggestions when a user enters a search string into a search box. The taxonomy may be implemented in a system (such as a commercial off-the-shelf content management system or SharePoint) that does not support the links/navigating to related concepts in the user interface. A taxonomy may be too small to make beneficial use of associative relationships if most of the taxonomy can quickly be browsed and seen. Finally, and perhaps of the greatest potential significance, is that relationships across different types of concepts can instead be better supported with customized semantic relationships based on custom schema and ontologies, which can be applied to a taxonomy. For example, having Physicians practice Medicine and Medicine isPracticedBy Physicians, instead of Physicians related Medicine.

It is not so much the presence but rather the extent of associative relationships that also distinguishes thesauri from taxonomies. In a traditional thesaurus, associative relationships are as prolific as hierarchical relationships, and perhaps even more so, and they occur between terms of all different kinds and different types of relatedness. The thesaurus standards (ANSI/NISO Z39.19 and ISO 25964-1) provide a list of possible types of associative relationships (process and agent, action and target, cause and effect, object and property, object and origins, and discipline and object, among many others). When taxonomies have associative relationships, they tend to be limited to only certain categories, facets, or concept schemes of the taxonomy.

Related Concepts and SKOS Concept Schemes

Most taxonomies these days, if they are of any significant size (hundreds or thousands of concepts) and intended for use in more than one application, are created in the SKOS (Simple Knowledge Organization System) data model. (Smaller taxonomies might be created in a spreadsheet and imported into a content management system.) The highest level of organizational structure in SKOS is the concept scheme. SKOS-based taxonomy management software will group and display multiple concept schemes together in a single “project” or “knowledge model,” which is intended for a single business use, set of content, user audience, or implementation (with some overlap of multiple use cases acceptable). While SKOS does not provide any recommendation on what you should use concept schemes for, it has become common practice to designate a concept scheme for a taxonomy facet or a metadata property/field. Even when concept schemes are not currently implemented as facets, they might be in the future, so it is good practice to created concept schemes to represent facets. The structure of concept schemes representing facets is also is also a good organizing principle for constructing any taxonomy. Concept schemes also tend to reflect top-level “classes” of ontologies (although not the very esoteric top class of “Thing”).

SKOS permits the creation of related concept relationships both within and between concept schemes. SKOS also has mapping relationships called matching properties, including relatedMatch, for use between concept schemes, whether they are in the same “project” (sharing the same, initial, domain part of a URI) or not. The option to use either related or relatedMatch across concept schemes of the same project can be a source of confusion.

Best Practices for SKOS Related Concepts

If you are implementing concept schemes each as a facet/filter/refinement in a user interface, then it is best practice not create associative (related) relationships between concepts in different concept schemes. Facets function as mutually exclusive aspects or dimensions of content items and queries. Any “relatedness” is implicit based on the search results, but not from the taxonomy itself, which should be flexible to allow any combination of concepts from facets and not prescribe relatedness. For example, a user may want to filter a search on movies by which movies meet selected criteria (facets) of a chosen genre, actor, director, topical theme, and country of production, and the result set will implicitly indicate in which movies where these aspects are related.

Enriching a taxonomy with the semantics of an ontology, in addition to supporting additional data attributes (such as movie production year, actor nationality and birth date, etc.), supports connections across concept types that can be utilized in a front-end application. The user can search not only for movies, but also search for other entities, such as actors (who appear in movies of a certain genre directed by a certain director), or directors (who directed movies on certain themes from certain countries), etc. This involved creating customized, semantic relationships between classes which correspond to the concept schemes: Actor performsIn Movie title and Movie title hasActor Actor, Movie title isProducedIn Country and Country isOriginOf Movie title, etc. These semantic relationships, of course, make any generic SKOS related relationships across the concept schemes unnecessary, redundant, and rather meaningless.

Thus, regardless of the use of your concept schemes, the related concept relationship is best not used between concepts in different concept schemes. Rather, the related concept relationship is better used between concepts within a concept scheme, especially topical (subject) concepts, for example, relating the concepts Data quality and Quality management. Relatedness between named entities within a concept scheme, on the other hand, such as concept schemes for People, Organizations, and Geographic places, is best left to be implicit from the retrieved content and not prescribed in a taxonomy, which may be dependent on the content, change over time, and be too subjective.

Even if the current end-user application of a taxonomy does not support user interaction with related links, associative relationships can support tagging, both manual and automated. Finally, a taxonomy typically has a longer life than a single application, so incorporating in related concept relationships while the taxonomy is being built and regularly maintained is a good practice for the future use of the taxonomy.